The experimental filmmaker, documentarist, and visual artist Barbara Hammer, who was born in Hollywood in 1939, has created one of the most influential oeuvres of Queer Cinema. Over the course of a lifetime, the pioneering lesbian film activist has put together a comprehensive manifesto of feminist perspectives.

Das Lebenswerk der 1939 in Hollywood geborenen Experimentalfilmerin, Dokumentaristin und bildenden Künstlerin Barbara Hammer hat die Geschichte des Queer Cinema mitgeschrieben. Seit 1968 hat die erste lesbische Filmaktivistin über 80 Produktionen mit dezidiert feministischer Perspektive vorgelegt.

Our first solo exhibition of Barbara Hammer’s work, in 2011, emphasized her contributions to the (self-)representation of lesbian love and sexuality in the 1970s; in this new show, by contrast, we focus on a parallel strand in her oeuvre that commences in the mid-1980s: Hammer’s engagement with illness, aging, and death.

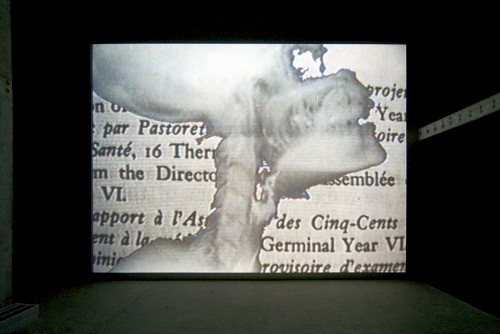

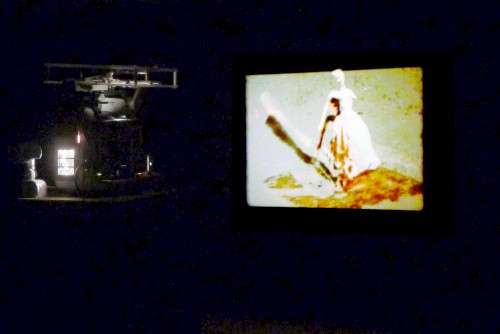

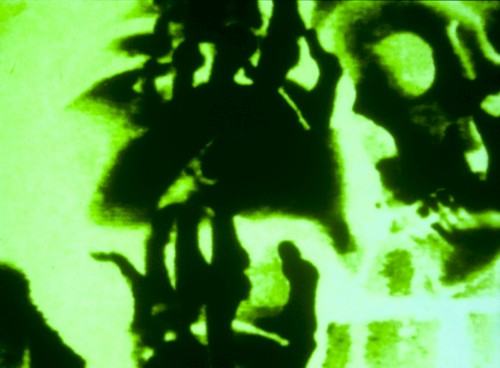

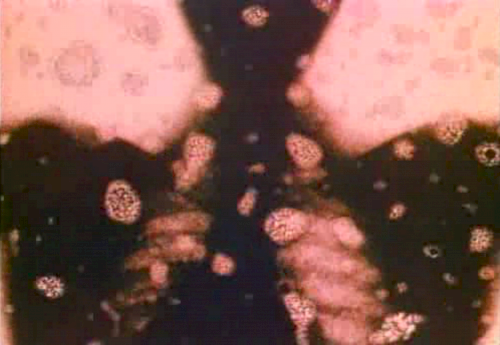

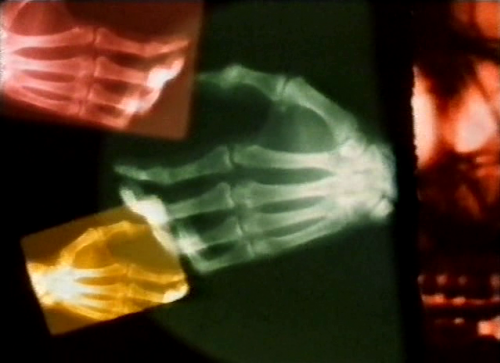

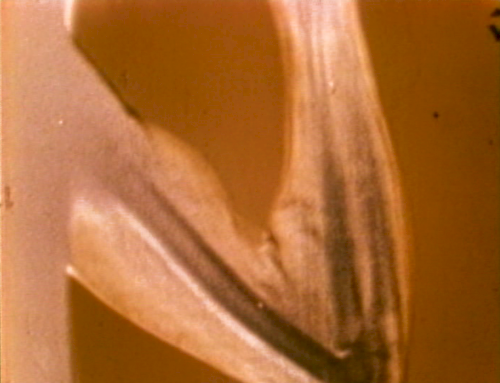

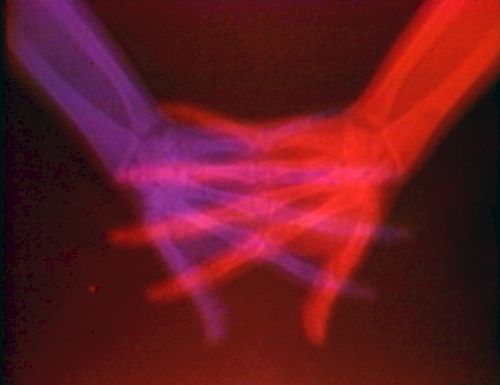

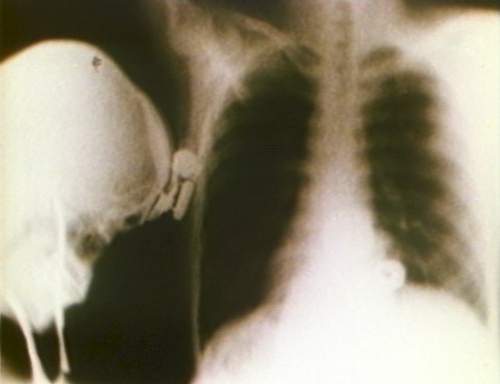

The centerpiece of the exhibition, which was designed in collaboration with the artist, is “Sanctus” (1990). Hammer uses moving X-ray pictures Dr. James Sibley Watson produced in the 1950s that capture—usually female—bodies in motion.(1) Watson had turned his study subjects’ bodies into a spectacle, subjecting them to visualization and medico-technical manipulation that cut to the quick; Hammer exalts these bodies, presenting them now as threatened, now as threatening, restoring their sensual presence. She copies, crops, and cross-fades Watson’s archival footage, painting on it and using chemicals to burn it. Hammer animates a danse macabre of female skeletons. This is more than a feminist and erotic reappropriation of the female body beset by technology and pathology—it is its canonization, supported on the original soundtrack by the composer Neil B. Rolnick’s computer-generated mass “Sanctus.”(2)

Zeigte unsere erste Ausstellung von Barbara Hammer 2011 vor allem ihren Beitrag zur (Selbst-)Repräsentation lesbischer Liebe und Sexualität in den Siebzigerjahren, konzentrieren wir uns nun auf einen Parallelstrang ihres Schaffens seit Mitte der Achtzigerjahre: Die Auseinandersetzung mit Alter, Krankheit und Tod.

Im Zentrum der gemeinsam mit der Künstlerin entwickelten Ausstellung steht „Sanctus“ (1990). Hammer verwendet Röntgenfilmaufnahmen, die Dr. James Sibley Watson in den Fünfzigerjahren herstellte, indem er Körper in Bewegungen durchleuchtete, meist Frauen.(1) Watsons kinetisches Spektakel der bis in ihre Tiefen visuell und medizintechnisch verfügbaren Probandinnen überhöht Hammer, zeigt diese mal bedroht, mal bedrohlich, und gibt ihnen eine sinnliche Präsenz zurück. Watsons Archivmaterial wird umkopiert und beschnitten, bemalt, überblendet und verätzt. Hammer animiert einen Danse Macabre weiblicher Skelette. Es ist mehr als eine feministische und erotische Rückaneignung des technisch und pathologisch besetzten Leibes der Frau - es ist seine Heiligsprechung, musikalisch getragen von der computergenerierten Messe „Sanctus“, die Neil B. Rolnick eigens komponierte.(2)

If no representation is available in which you recognize yourself, then represent yourself.

Wenn keine Repräsentation verfügbar ist, in der du dich wiedererkennst, dann repräsentiere dich selbst.

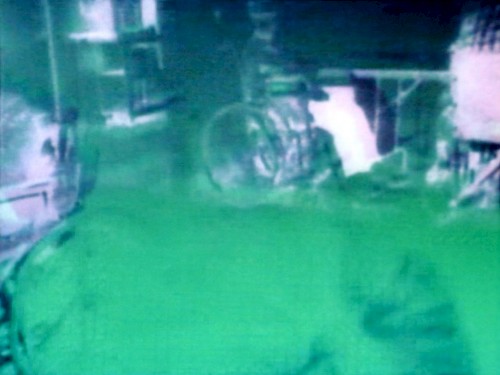

Like “Sanctus,” “Optic Nerve” (1985), Barbara Hammer’s contribution to the 1987 Whitney Biennial, is a principal work of her experimental practice. The film is based on 8 mm footage showing her 97-year-old grandmother. Physical decline, the life-sustaining function of medical equipment, the sense of being at the mercy of time and technology: Hammer figuratively applies these to her own use of the celluloid material and the creation of the soundtrack. The result is a disturbing dovetailing of the physiological and filmic apparatuses. The grandmother’s blindness in one eye, her loss of spatial vision, leads Hammer to the limits of her medium, away from the naturalism of three-dimensional visualization and toward an existential minimalism: “Optic Nerve” turns into a flickering, hazy, mechanical conglomerate, a filmic portrait on the edge of vision.

In “Vital Signs” (1991), Barbara Hammer demonstratively transforms the horror of death into its opposite. She tenderly cares for a human skeleton, feeding it, dressing and caressing it, taking it for walks in the dark cabaret of an intimate relationship beyond death. She confronts pain and fear rather than repressing them. In 1986, she makes “Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS,” in which she examines the public ignorance, stigmatization, and instrumentalization of illness and death. For “8 in 8” (1994), which criticizes the media’s coverage of breast cancer, the artist shoots her own interviews with patients. In a programmatic act, she transfers newspaper reports about rising cancer rates, therapies, their consequences and marketing onto bones.

In 2008, her perspective shifts. “A Horse Is Not a Metaphor”(3) documents her own struggle with cancer. Hammer shoots inside the hospital, where she herself is now an object in the medical apparatus; filming serves her as a way to maintain her own subjecthood. The digital handheld camera coolly registers her ailing and swollen body under clinical observation. The film “is an undisguised bit of activism, a frank plea for survival, and an everyday chronicle of what a person must endure.”(4) Hammer’s presenting herself in this fashion is not an act of narcissism. Since the early 1970s, her films have put a feminist demand that is also a core piece of democratic culture into practice: if no representation is available in which you recognize yourself, then represent yourself.

(1) In “Dr. Watson’s X-Rays” (1991), Hammer documents the circumstances in which the film was made and its repercussions.

(2)/(4) See Ara Osterweil, “A Body Is Not a Metaphor: Barbara Hammer’s X-Ray Vision,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 14, no. 2–3 (2010).

(3) Music: Meredith Monk.

Text and Photos: Alexander Koch / Translation: Gerrit Jackson

„Optic Nerve“ (1985), Barbara Hammers Beitrag zur Whitney Biennial 1987, ist wie „Sanctus“ ein Hauptwerk ihrer experimentellen Praxis. Sie arbeitet mit 8mm-Aufnahmen ihrer 97-jährigen Großmutter. Den körperlichen Verfall, die Lebensfunktion medizinischer Geräte, das Ausgeliefertsein an die Zeit und an die Technologie, überträgt Hammer auf ihren Umgang mit dem Zelluloid-Material und auf die Gestaltung der Tonspur. Ihr gelingt eine bestürzende Verschränkung von physiologischer und filmischer Apparatur. Die Erblindung der Großmutter auf einem Auge, der Verlust des dreidimensionalen Sehens, führt Hammer dabei an die Grenze ihres Mediums, weg vom Naturalismus räumlicher Darstellung und hin zu einem existenziellen Minimalismus: „Optic Nerve“ wird ein flackerndes, verschwommenes, mechanisch zusammengehaltenes Filmportrait am Rande des Sehvermögens.

In „Vital Signs“ (1991) wendet Barbara Hammer den Schrecken des Todes demonstrativ in sein Gegenteil. Sie schenkt einem menschlichen Skelett ihre zärtliche Fürsorge: Sie füttert, kleidet und liebkost es, führt es spazieren in der dunklen Revue einer innigen Beziehung über den Tod hinaus. Sie konfrontiert Schmerz und Angst, statt beides zu verdrängen. Die öffentliche Ignoranz, Stigmatisierung und Instrumentalisierung von Krankheit und Leid untersucht sie 1986 in „Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS“. 1994 kritisiert sie mit „8 in 8“ die Medienberichterstattung über Brustkrebs und dreht eigene Interviews mit erkrankten Frauen. Programmatisch bedruckt sie Knochen mit Zeitungsberichten über die Zunahme von Krebsfällen, über Therapien, ihre Folgen und ihre Vermarktung.

2008 ändert sich dann ihre Perspektive. „A Horse Is Not a Metaphor“(3) dokumentiert ihren eigenen Kampf mit dem Krebs. Hammer filmt im Krankenhaus, nun selbst Objekt in der medizinischen Apparatur, und sie filmt, um sich darin als Subjekt zu behaupten. Kühl registriert die digitale Handkamera ihren angeschlagenen, geschwollenen, klinisch observierten Körper. Es ist „ein unverstelltes Stück Aktivismus, ein offenes Plädoyer des Überlebens, eine alltägliche Chronik dessen, was eine Person aushalten muss“.(4) Dass Hammer sich so darstellt, ist kein Narzissmus. Seit den frühen Siebzigerjahren setzen ihre Filme eine Forderung des Feminismus und einen Kern demokratischer Kultur ins Werk: Wenn keine Repräsentation verfügbar ist, in der du dich wiedererkennst, dann repräsentiere dich selbst.

(1) In „Dr. Watson’s X-Rays“ (1991) dokumentiert Barbara Hammer Hintergründe und Auswirkungen der Filmproduktion.

(2)/(4) Vgl. Ara Osterweil: „A Body Is Not a Metaphor: Barbara Hammer’s X-Ray Vision“, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Volume 14, Issue 2-3, 2010

(3) Musik: Meredith Monk

Text und Fotos: Alexander Koch

- Current

- Upcoming

- 2026

- 2025

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009