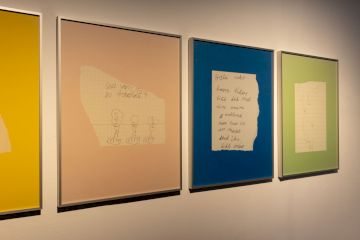

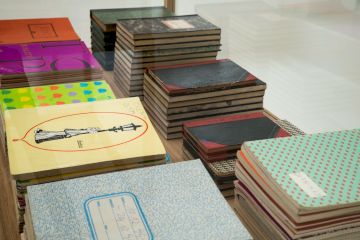

Archives are ambivalent places. While accumulating materials for the possible reconstruction and visualization of historical events, they also generate invisibility: sometimes the most illuminating sources turn out to be those that never entered distinguished archives. Friedl’s long-term project Theory of Justice (1992–2010) is a collection of these blind spots in our visual memory. Without any claim to totality or objectivity, the pictures in Theory of Justice are dedicated solely to the chronology of the documented, depicted events and otherwise are motivated by a poetic, and anti-archival drive. Rather than mere confirmations of existing knowledge, the images are supposed to serve as trails to the “optical unconscious” (Walter Benjamin). The spectrum ranges from strikingly iconic pictures of protest to intimate portraits whose political significance only become apparent on a second glance. Friedl’s source material derives from an array of different newspapers and magazines.

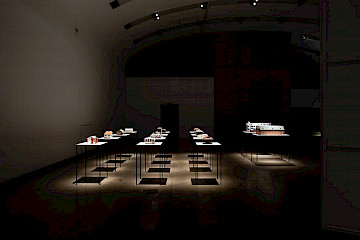

The title refers to A Theory of Justice, the famous 1971 book by American philosopher John Rawls. According to his main thesis, social and political processes function due to the willingness to balance interests and reach a consensus. However, the images in Theory of Justice show that consensus has progressively been replaced by conflict, especially in the age of global neoliberalism. The title is not just a laconic comment on Rawls’s theory—it is also programmatic: as a reference to the need for a new theory of justice. Theory of Justice can be interpreted as a model of “pictorial justice.” The selected newspaper images are granted “a new chance on another time level” (Friedl). Freed from their contexts and arranged in a precise time grid, the images begin to convey the basics about the structure of political protest and resistance; thus isolated, each picture is made available for a broad range of possible interpretations and meanings. The political artefact becomes an aesthetic artefact.