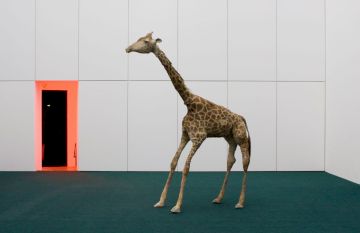

Peter Friedl’s Everyone is a conspiracy theorist, is a shack-as-model. It hangs atilt from a wedge-shaped wall platform, on the verge of tumbling down. Friedl has painstakingly recreated the cabin in which Charlie Chaplin finds refuge high up in the snowbound mountains in The Gold Rush (1925)—and which, near the end of the film, crashes down from the mountaintop seconds after Chaplin and his fellow prospector Big Jim have escaped in a bravura slapstick performance.

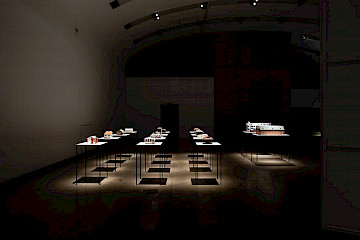

Yet this isn’t about Chaplin. Friedl repurposes a famous and widely circulating image. In reconstructing the film cabin, he revisits concerns he already grappled with in the architectural models in his Rehousing series (2012–19): if new structures are typically built after maquettes, though the finished buildings never quite resemble those models, model-like reconstructions of existing (and, a fortiori, of vanished) buildings are conversely never exact replicas of reality. They’re approximations, in part imaginations—a critique of realism that cuts to the heart of art’s role.

Friedl’s approximation of the cabin from The Gold Rush further complicates the process. When the black-and-white movie was made a hundred years ago, film historians believe, different mockups of the cabin were used for exterior shots and, in the studio, for interior scenes. Friedl’s shack, by contrast, is real and in color, meticulously executed down to the smallest detail. It’s not a representation—it’s an image. A very accurate image that asserts its aesthetic autonomy and indeed constructs it through the subtraction of context (film) and the reduction to visual contemplation. A stratagem characteristic of Friedl’s oeuvre.

And so a small cabin hangs on the gallery wall and threatens to tumble down from its podium, though—being a sculpture—in the end it doesn’t. Making its precariousness a permanent state of affairs, the work urges us to see it as an allegory. It’s a simple, humble dwelling; millions of its kind exist all over the world. That it’s teetering on the edge of an abyss is something millions of people in 2023 would confirm, were one to ask them about their circumstances and future prospects, about the angle of inclination of their own shacks and existences.

In 1925, The Gold Rush gave a haunting portrait of precarious living circumstances and the capitalist dynamics that underlay them. The reasons for such precarity? Complex, then as now. And there is no single truth that explains it all. Everyone is a conspiracy theorist—because to explain such vast and varied imbalances we have no more than models. Approximations. Attempts to grasp the real and give a name to the positions of our own shacks. Something must have happened for so much to be teetering on the edge. But what was it?

History doesn’t provide answers, or succor. Friedl’s shack is empty, the door is wide open, whoever was inside has fallen from it. There’s nothing left to correct or rebalance. Lopsided is lopsided, and crash is crash. It’s a somber, a pessimistic work that Peter Friedl has made. Even the greatest precision in the (re)production of ostensible facts cannot but bring us back to the one reality that the shack is, and remains, atilt.